It is often said that cruisers are obsessed with weather. In this article, Katja discusses her techniques for interpreting the masses of data available in her favorite weather app and how to make sensible decisions about when it is save to head out to sea.

Whether you are at anchor, sailing from one anchorage to another or doing a passage, weather rules your day. The days that we downloaded a forecast made by a meteorologist and watched the barometer are gone, today everybody checks the weather on Windy. But nobody interprets the endless animated data for you, as we learned when cross waves that we hadn’t seen forecasted made us abandon the first passage with our new boat.

Forecasting the wind

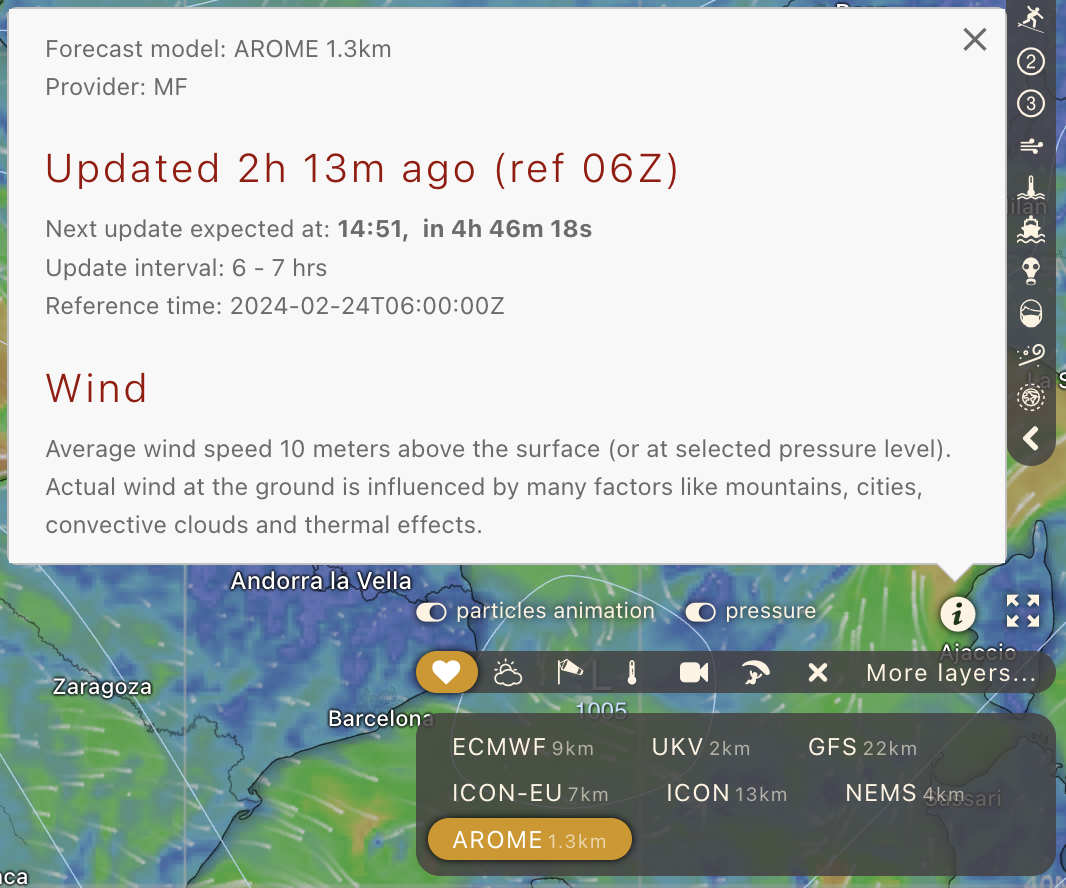

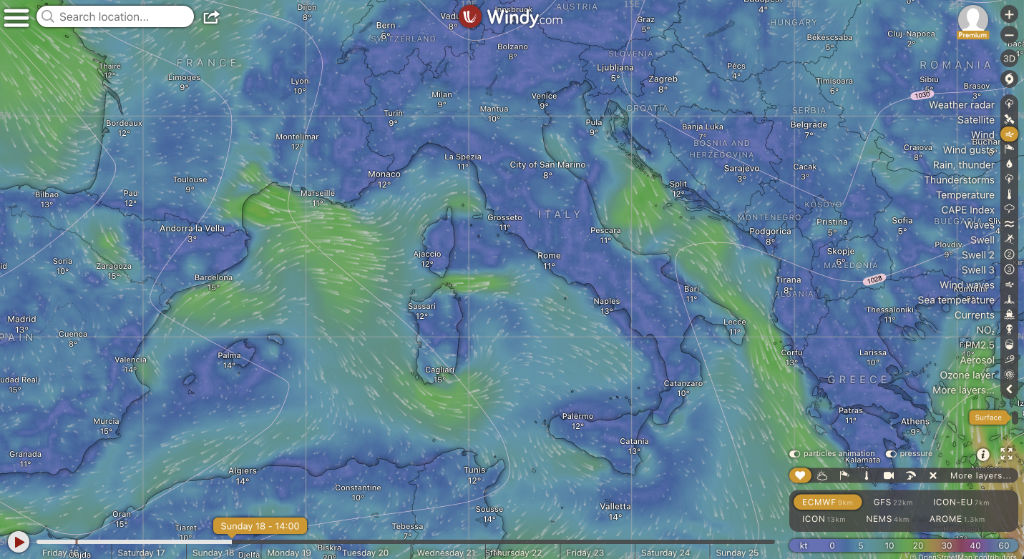

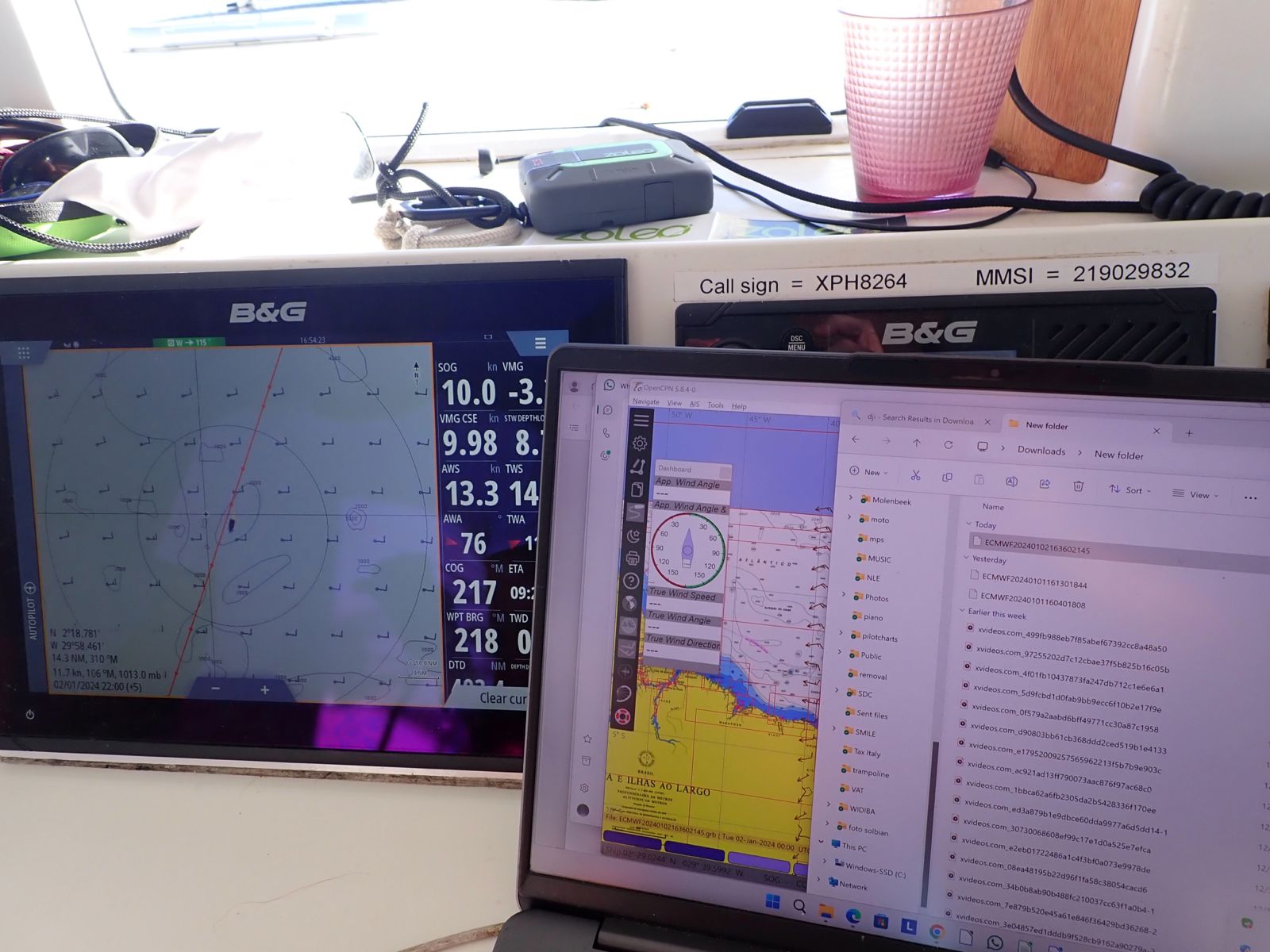

Windy displays many different wind models. The world is covered by three main forecast models: ECMWF, GFS and ICON. Several other local models show up when you zoom into an area too.

When comparing the different models you soon realise that weather forecasting is not an exact science. The models merely depict the probable outcome of a continuous 3D interaction between water, land and the air above. Unfortunately there is very limited real data creating great uncertainty in the outcome of those interactions. In the central Mediterranean Sea where pressure lines are often very scarce, a common motto is: “expect the wind as forecasted plus or minus 3 Beaufort.”

When looking at the Windy wind map, it is a good idea to check all the available models and give most attention to the model with the smallest grid size since it is more likely to pick up local weather disturbances. For example, the Medicane that hit Corsica in August 2022 was only visible on Arome with its 1,3km grid. Press ‘info’ to check when the model was last updated. Then, to be on the safe side, take the wind gusts as a reference not the mean wind, especially if on a catamaran that cannot discharge the force of the gust by heeling.

Limitations

The forecast models do not take the influence of land into account. So it is perfectly normal to sail with a pleasant afternoon breeze, or to experience strong katabatic winds when anchored below steep cliffs despite Windy showing zero knots in your location.

Squalls (isolated local thunderstorms) aren’t forecasted at all, although you can check the CAPE index for upcomming thunderstorm probability. Beyond that you will have to look at the sky and the radar (targeting them with EBL lines) to learn how squalls approach and effect you. As a general rule, in the Northern hemisphere squalls at about 30 degrees to the right of the true wind will head towards you. In the Southern Hemisphere they arrive from the left of the true wind.

Forecasting the waves

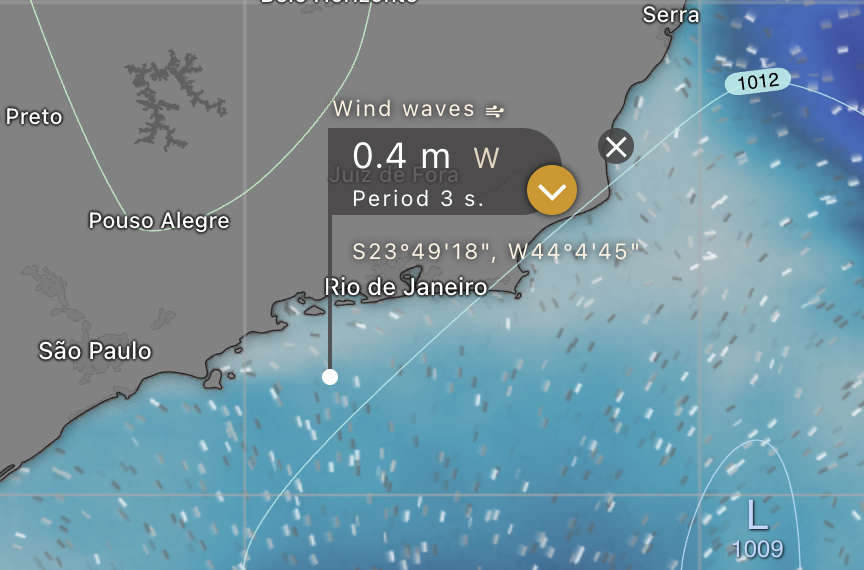

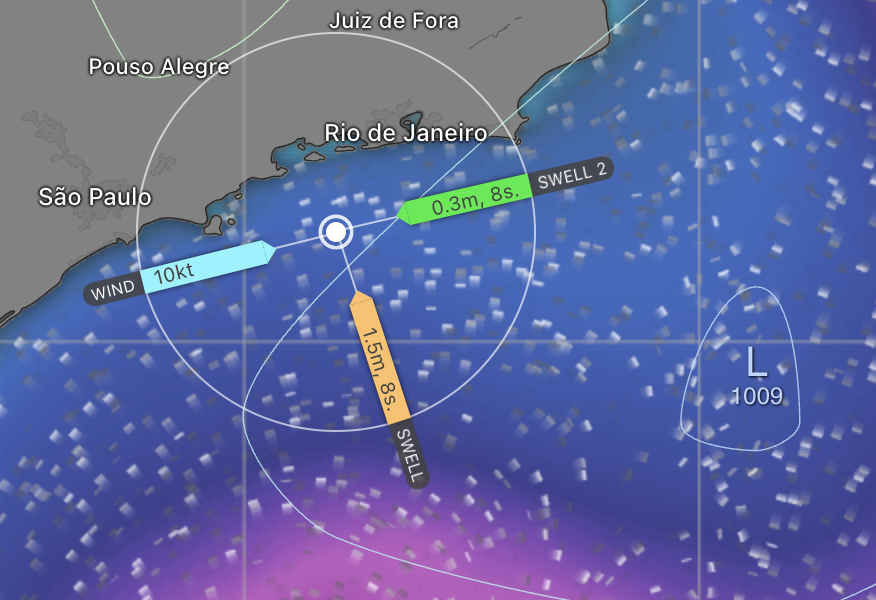

Windy includes a wave map. When you click ‘waves’ on any given position it shows a wave rose with three arrows labeled ‘swell 1’, ‘swell 2’ and ‘wind’ respectively. To see the waves that the wind creates, you will need to switch to the ‘wind waves’ map.

Wave properties

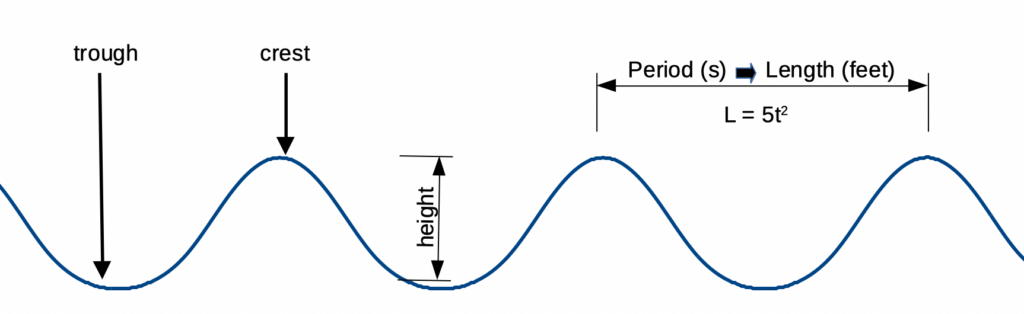

Waves have three main properties: 1) direction as indicated by the arrow on the map, 2) height as indicated in the arrow according to the unit set by you and 3) time in seconds from one crest to the next, called the period.

The forecasted wave height is the ‘significant wave height’ (SWL) which is the average hight of the highest one third, so you will experience higher waves (apparently 1 in 2000 waves will be twice as high). The forecasted wave period is used to calculate the wave length which is, in feet, five times the period (in seconds) squared.

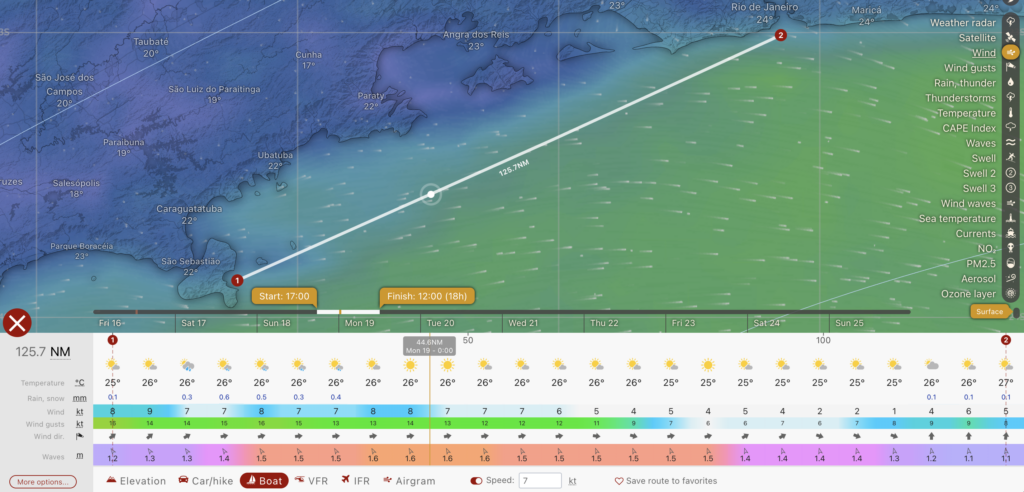

Using the formula, the wind waves in front of Rio de Janeiro in the example above (10 knots from WSW creating waves of 40cm with a 3 seconds period) are 45 feet (14m) long. For curiosity we can calculate the slope percentage (0.4/7×100) which turns out to be a little less than 6%. Which is steeper than a ten times higher wave, a wave of 4m, when the period is 10 seconds. So always check the combination height and period before judging the wave forecasted.

Wave influence

The influence of the waves depends on your boat, whether it is a mono- or multihull, the waterline length, the shape of the hull(s) and the type of keel, amongst others. When changing from a fin keeled monohull to a performance catamaran (both 49 feet) the effect of the waves was a big surprise to us. High waves from the aft quarter are fine on our catamaran and forgotten are the days when we rolled down one wave after another one on our monohull. Waves forward of the beam are a different story as they make our catamaran slam whereas the monohull just drove through them lying gently on its side. Short waves from the beam are always uncomfortable but for different reasons. The natural roll of a monohull can be amplified by the wave period whereas on a catamaran the two hulls touch different parts of the wave.

Concerning swell at anchor there is no comparison, life at anchor is what cats are made for! Therefore, when looking at noforeignland anchorages just check the type of boat the reviewer sails before fully relying on their review.

Wave forecast limitations

When the Windy wave rose depicts waves from different directions, expect confused seas with steeper waves than those visible in the wind rose. Also, be aware that Windy does not consider land shelter (i.e. anchorages!) and that it displays the waves developed with full fetch. The effect of (tidal) current on the waves, where counter current makes the waves steeper, is not considered either.

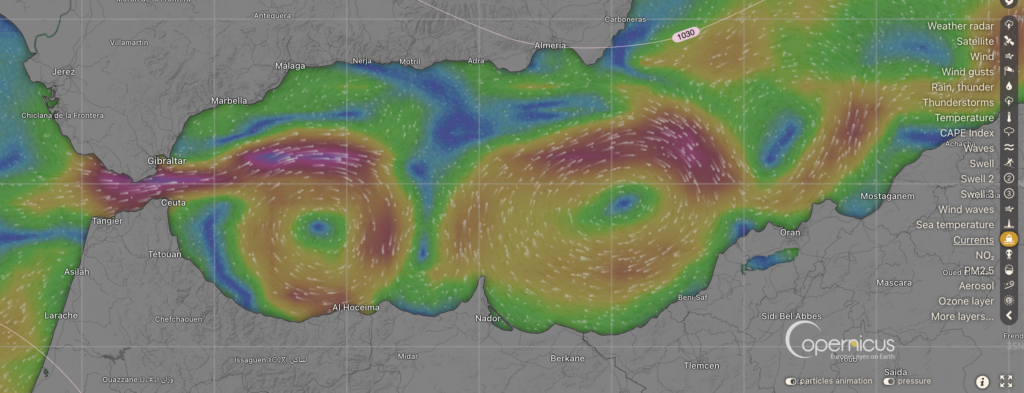

Other Windy data

Windy has a long list of other useful data. We like to display the pressure lines to visualise weather fronts. We also check the CAPE index as an indication for possible lightning. You can also see currents when sailing around islands or as shown in the above screenshot: in the Straight of Gibraltar. It’s also nice to check the weather radar for thunderstorms and the hurricane tracker.

Departure planning

While long term passage planning can be done using pilot charts, imminent trips can be planned with Windy’s Distance and planning tool.

The Distance and planning tool only works with the ECMWF model and a fixed boat speed (as opposed to a polar) but we find that when looking at the wind direction/speed it is easy to guesstimate a workable average. This is because boat speed on passage is often a question of choice as cruisers are not racing against their polar but seeking a more comfortable passage.

When a trip lasts longer than a few days, forecasts need to be updated given their short expiry date. Yes, I know that the models forecast up to two weeks but anything past four days is based on so many assumptions that it often becomes guesswork and not something to base onboard decisions on.

Our practice

Like all cruisers, we try not to sail upwind when we can help it (it can be a slow and uncomfortable ride). Beyond that it is the wave situation that dictates the trip on our catamaran. As a rule of thumb we postpone the departure when the route pictures waves at an angle of less than 120 degrees with periods shorter than 5 seconds (when height >1m) or shorter than 8 seconds (when height >2m). When the swell and wind aren’t from the same direction we also think twice.

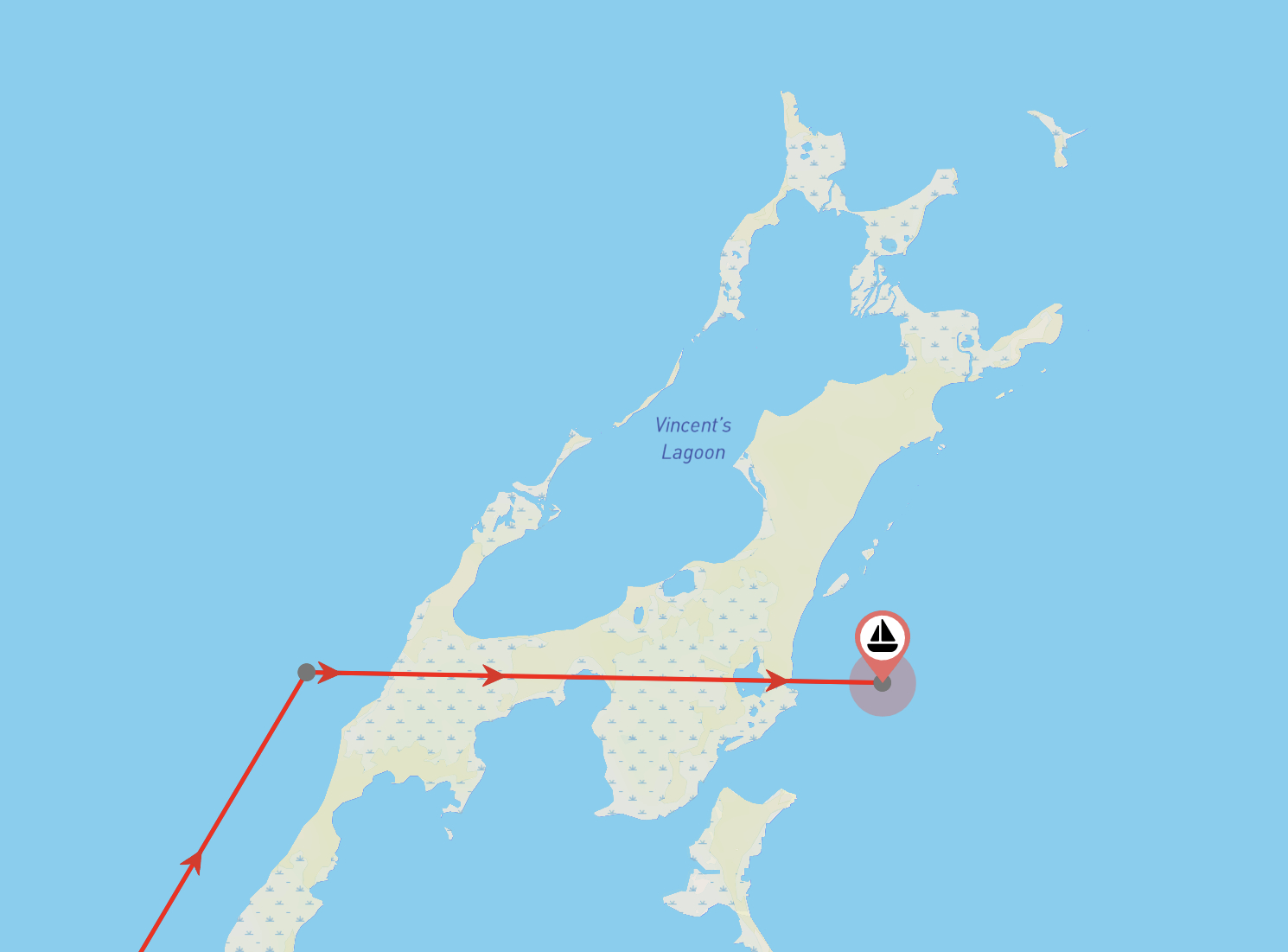

On our first big trip, when we set out from The Netherlands to the Northern point of Denmark with a building easterly in the German Bight, we simply hadn’t paid attention to that third arrow (‘wind’) on the wave rose that indicated 1.5m cross waves with a 4 seconds period. The sea conditions on that day taught us a hard lesson and led us to abandoning the passage.

We find it pays to check the maps every day and learn how the weather evolves as the day unfolds. This is particularly true when you find yourself in a new continent. We realised here in Brazil that our European weather experience served little to help is understand the weather patterns in South America. So, we talk to the locals and try to learn.

We are pretty confident in our ability to predict sea state for our trips, but you never really know what you will get until you are out at sea. If you have any further tips on how to use Windy, or tricks that you’ve learned over the years, please comment below and let us know.

Fair winds and enjoy the cruising life!

Hi Katja. Great blog. I use windy a lot and in addition to the features you mention above, I look at the predicted rain charts for long distance planning. I find that knowing the predicted rain conditions helps me pick out the fronts and also developing fronts that are not obvious from the pressure charts. I also use predicted rain to serve as a warning for squally conditions. Especially useful here in Brazil, when new lows seem to develop out of nowhere! Safe travels, Lin

Thank you Lin! Indeed the predicted rain conditions is also very useful data. I smiled at your comment about sailing in Brazil, it is spot on: the way the weather develops is so different to what we are used to in Europe. Enjoy your travels on Velvet Lady and hope to meet again, Katja

Great article! Can you tell me more about the formula for calculating the wave slope percentage (0.4/7×100)? The numerator (0.4) is the wave height in meters. Where did the denominator (7) come from?

Thank you,

John

Thank you John for your comment!

I use slope percentage for the ratio between elevation over a horizontal distance: elevation/distance x 100 (so a 45 degrees slope has a slope percentage of 100%). Of course this is average since a wave does not have a constant slope from trough to crest.

In the example above (wave 40cm high with 3 seconds period) the distance from one crest to the next is almost 14m (L=5t^2 in feet). The distance from trough to crest is half of that wavelength, hence the 7m, making the (average) slope percentage 5,7%. The 4m wave with a 10s period is 152m long (so distance trough to crest is 76m) has a slope percentage of 5,3%.

Since the waves relate directly to the comfort onboard, we never judge the waves without calculating their length. For example our 8m wide cat ‘wobbles’ on a 3 seconds cross wave as one hull is on the crest and the other in the trough.

Thank you for taking your time to read and comment.

Fair winds!

Katja