A remote area cruiser exploring the world aboard his Passport 545CC, Walt shares his thoughts on the role fuel plays on their vessel. He explains the benefits he’s experienced having larger long-range tanks, and details how he calculates range under power, to know how much further he can go with the fuel he has aboard.

When you’re cruising the coast, fuel isn’t usually top of mind; the next dock is never far away. But once you step into the world of offshore voyaging and remote anchorages, the equation changes dramatically.

Out there, diesel isn’t just about turning the propeller. It represents safety, independence, and the ability to live comfortably away from land. For the modern blue water sailor, fuel capacity is one of the defining traits of a true passage maker.

From tradition to today

In the 1960s and 70s, plenty of voyaging designs carried very little diesel. Some dispensed with an engine altogether. These boats were built in an era before energy-hungry systems; no refrigeration (or just an icebox), windvane steering instead of powered autopilot, no watermaker, no radar, and certainly no satellite internet. A kerosene lamp and a sextant were all that most sailors needed.

Today, things are different. The modern voyaging yacht often has both a refrigerator and freezer, autopilot, watermaker, high-output communications, and a full suite of electronics. Solar and wind cover much of the load, but not all. In weeks of cloudy skies, or in the shorter days of the tropics, battery banks can struggle. That’s when having diesel-driven charging capacity, a generator or a high-output alternator on the main engine, becomes essential.

Fuel as a safety margin

Diesel isn’t just about comfort; it’s about resilience. Offshore, hundreds of miles from shelter, a dismasting or rigging failure could mean days of motoring. Even without a catastrophe, having enough fuel gives you options. Take the ITCZ as an example. Crossing it often means alternating between dead calms and violent squalls. On Wanderlust’s last passage through, I put in and shook out a reef at least eight times in a single day, while motoring for about six hours through calms to weave around the worst squalls. Without fuel in reserve, you’re at the mercy of whatever comes next. With it, you can maneuver, stay in control, and keep the passage safe.

Some traditionalists argue electronics aren’t essential, that a “real” sailor should simply ride it out under sail alone. I see it differently. Seamanship is about making good decisions with the tools available. Reliable weather data, for example, enables smarter routing, and smarter routing is safer. Access to that information requires energy, and offshore, energy ultimately comes from fuel. Using diesel to avoid punishment, preserve crew and gear, and keep critical systems – autopilot, navigation, communications – alive isn’t weakness. It’s prudence. That combination of mobility and power is one of the truest safety margins at sea.

The freedom factor

One of the greatest joys of a capable offshore sailboat is the ability to disappear into remote anchorages for weeks at a time. Fuel capacity is what makes that possible. With ample diesel on board, you can make your own water, keep the refrigerator running, and charge batteries without being tethered to a marina.

On Wanderlust, our 2014 Passport 545AC, we carry 376 gallons in three stainless steel tanks, all positioned low in the bilge. That keeps weight centered and the foredeck free of yellow jugs lashed to lifelines. More importantly, it means we can reach places where the nearest fuel dock is hundreds of miles away, or may not exist at all. In the Tuamotus, for example, fuel is scarce and expensive. Because we have the reserves, we can drop anchor in an atoll and stay as long as we want, running systems as needed, without constantly rationing every amp-hour while worrying about the next refueling run.

This is where tankage turns from numbers into lifestyle. With it, you can live off-grid, self-reliant, and free to explore on your own terms. Without it, your horizon shrinks to the distance between fuel docks. For us, generous built-in capacity has meant crossing oceans without worry, lingering in places we love, and truly living the sea gypsy life.

Tankering: A practical advantage

Large tanks have another benefit; economics. Diesel prices fluctuate wildly by region. With big tanks, you can “tanker” fuel, buying in bulk where it’s inexpensive and carrying it forward.

Since leaving San Diego in February 2023, we’ve bought fuel only in San Diego, La Paz, Tahiti, and New Zealand. Before sailing from New Zealand back to French Polynesia in March 2025, we topped off again. After the 2,500 nautical mile passage and months of cruising Tahiti, Moorea, Raiatea, Tahaa, and the Tuamotus, we still have half our supply left. That kind of range changes the way you voyage.

How to calculate range under power

Knowing how much diesel to carry is one thing. Knowing what it gives you in real terms is another. Calculating your range is straightforward if you know two things:

- Fuel consumption at cruising RPM (gallons per hour).

- Average boat speed at that RPM (knots).

The basic formula is:

Range = Usable Fuel x Speed/(Burn Rate)

For imperial units, range is in nautical miles, usable fuel in gallons, speed in knots, and burn rate in gallons per hour.

For metric units, range is in kilometers, usable fuel in liters, speed in kilometers per hour, and burn rate in liters per hour.

A few key points:

- Always use usable fuel, not total tankage. Most tanks can’t be completely drained without sucking up sludge or air.

- Average speed should be based on real-world conditions, not just flat-water sea trials.

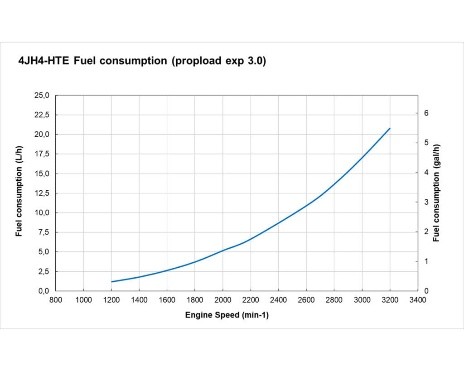

- Fuel burn curves (often in the engine manual) are a good starting point but confirm them with actual log data.

The Wanderlust Example

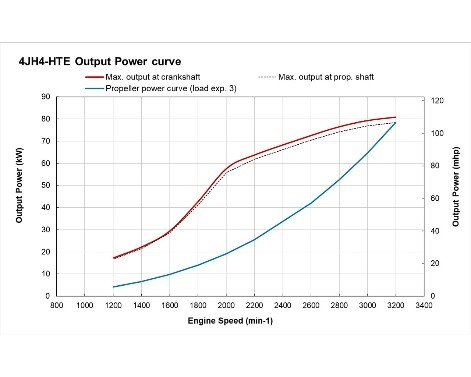

On SV Wanderlust, we run a Yanmar 4JH4-HTE:

- Cruising RPM: ~2000

- Burn rate: ~1.3 gph

- Usable fuel: ~350 gallons (out of 376 total)

- Average speed at 2000 rpm: ~6.5 knots

Plugging into the formula:

1,750 nm = 350 Gal x (6.5 kts)/(1.3 GPH)

That’s unusually generous for a 55-footer. A more typical target for a true bluewater boat is the ability to motor 1,000–1,200 nautical miles. This gives enough reserve to handle calms, detours, or emergencies.

The critical lesson is to know your numbers. If the manufacturer doesn’t provide a curve, measure your own consumption in calm conditions and log it against RPM and boat speed. That knowledge isn’t trivia; it’s a planning tool and a genuine safety margin.

How much is enough?

Every skipper’s answer depends on their boat, cruising style, and appetite for risk. But for a 45–55 foot passage maker, 250–400 gallons is a proven sweet spot. Smaller boats can get by with less, but the same principle applies; capacity equals freedom.

Freedom and safety through fuel

Diesel tankage is more than steel or fiberglass tanks filled with liquid; it’s stored freedom. It lets you cross oceans, sit happily in remote anchorages, tanker fuel when prices are low, and keep essential systems alive even in poor weather.

In the end, the right amount of fuel isn’t measured only in gallons. It’s measured in freedom, safety, and the kind of cruising life you want. If your dream is to cross oceans, stay far from the beaten path, and choose your own horizon, then generous, well-designed fuel capacity is what transforms a capable sailboat into a true bluewater cruiser.

If your only or primary source of power generation is a diesel engine then yes, huge capacity is required for remote cruising. But if you can also generate electricity from sun, wind and water, then diesel is primarily required only for propulsion. 1000nm motoring range is plenty, assuming that you are also willing to sail even when boat speed is not that much. Unless you’re planning to sail in far northern latitudes, that’s a use case for huge diesel reserves.

And, while diesel doesn’t perish over time in the same way as gasoline, it’s still not a bad idea to have multiple smaller tanks and/or jerry cans rather than a few huge tanks.

Your premise suits your type of yacht, but it isn’t universally applicable.

This exactly. Thanks for pointing out that this is truly a “my boat” perspective and is not a universal truth.

As usual, the answer to any question about cruising needs to start with “it depends”.

Wanderlust has ~1800 Watts of solar panels and two 550 Watt hydrogenerators (one for each heel) so, I agree with you those are the primary charging sources. However, in short winter days in the tropics combined with a few overcast days and a backup charging source is still needed. For that purpose, we have a diesel generator which is much more efficient than using the main engine.

I disagree with your comment about tanks. IMO, a few, larger tanks down low in the boat that are well maintained are significantly better than jugs lashed on deck. With our Racor filters, the fuel in the tanks is kept clean whenever we run a diesel engine and, if we don’t for a long period, we have a separate filter with a small transfer pump to filter the diesel and, if necessary, move it between tanks.

I generally use the term “off grid” as off the diesel distribution grid as well. Diesel does not equal freedom, renewable energy does.

I would love to say you are 100% correct but, in my experience, I can minimize the amount of fossil fuel I burn but haven’t been able to totally eliminate it and live the lifestyle we prefer. Several cloudy days combined with short, winter days and longer nights in the tropics mean our 1040AH battery bank isn’t enough.

There’s obviously been a lot of thought put into this article, all of it based (as expected) on a very personal use case.

Respectfully, I think a more accurate statement is that self-sufficiency, not fuel capacity, is the true hallmark of a modern voyager. The primary safety valve is solid sailing skills, not a bigger diesel tank.

On our 28’ cutter, we have all those modern conveniences you mentioned other than a freezer. We’re heading into month 5 of our Tuamotus exploration and have happily made water, charged electronics, fired up Starlink to check weather, and lived without monitoring every amp. Without once relying on the diesel engine for charging or even needing to pull out our small gasoline auxiliary generator.

For those reading who have neither a 55’ boat nor the capacity for 350 gallons of diesel, take heart.

I totally agree about being self-sufficient and we each have to decide what that means. This article was about fuel capacity because that can be an important factor. As I mentioned, many sailors have sailed for years with no engine and no electricity (the Pardeys for example) and were content.

You choose to keep your Starlink off and “fire it up to check weather”. That saves a lot of power. I choose to leave mine on 24×7 and upgraded the solar to handle the additional load. Yet, we chose to forego a freezer as we didn’t think it was worth the extra power consumption

Unfortunately you wrote this article as if this fuel capacity is essential for everyone (see the title) because it is for you. You need to fire up your generator frequently, part of why you need such fuel capacity. We opt for a mini that we can turn off if we’re needing to conserve power as opposed to disturbing the peace of an anchorage by firing up a generator.

The Pardeys were outliers even when they cruised on Serrafyn. Using them as a an example of “many” is as extreme as saying a true blue water cruiser needs to carry 350+ gallons of fuel.

I’m sorry you didn’t couch this article in more personal terms. Just because massive fuel capacity is essential to you does not make it a cruising maxim. There’s a lot of information in here that is just false because you’ve shared your truths as universal ones.

I’m sorry if my article is a bit confusing. I was trying to highlight what I think a bluewater cruising boat’s fuel is used for and simply using Wanderlust as an example of how I met those needs. In the article, I even say that Wanderlust’s fuel capacity is overkill. Since she is semi-custom, I added a fuel tank in an available bilge space that wasn’t useful for much else.

I’m also NOT saying everyone else has the same criteria we have but pointing out what having a relatively large fuel capacity gives us.

Having said that, I do stand by my most of my general statements. As I have said other places, almost any boat can do bluewater cruising but if they’re not designed for it there are consequences. My goal is to spark discussion and get people to think about what they want and then make the right choices for themselves.

Since COVID, I have seen/read about too many people just buying some boat without understanding what bluewater cruising actually entails then getting in trouble. And, let’s face it, modern technology provides a huge safety margin (GPS, chartplotters, radar, AIS, StarLink, etc.) but they all consume energy and even with solar panels and other renewable energy sources, sometimes it is still necessary to run a generator to keep the batteries charged.

Most of my cruising philosophy is about self-sufficiency. The main point I want to reiterate is I believe a bluewater boat should have enough motoring range to be able to reach safety if something goes wrong. Additional considerations are how long you want to remain in remote anchorages combined with what your ‘on the hook’ lifestyle is. I know many cruisers, typically in catamarans, that want to run AC, two freezers, a refrigerator, large screen TV, etc. and run their generator many hours per day. Others use almost no electronics and live a more minimalist lifestyle.

It’s a spectrum and each cruiser has to decide for themselves but they should make conscious choices.

Wonderful perspective Nica, thanks for sharing. Often life will teach us the lesson that “less is more.”

Ice off the grid is a blessing and a curse. We do make ice in our freezer, and for us ice in the tropics is a blessing, but we suffer the curse of running a generator daily to have it. Our 46′ monohull does not have room for enough solar panels to remain sleek and still keep up with our refrigeration power demands in the tropics. But, with only 55 gallons usable diesel in our tank and some jugs on deck, we have spent 3 months at a time in uninhabited places, and never run out of ice or diesel. If you have a boat that sails well in very light wind, and the patience to sail slowly when necessary, most self-reliant sailors can find a way to do what they want to do with the fuel capacity they have.

No disrespect intended to Walt. I think his analysis and perspective was very helpful to prompt others to consider and evaluate their own capacities, priorities, and requirements and I thank him for sharing. Would I like more fuel capacity? Of course I would. Would I like a heavier boat that did not sail as well in light air? Of course not. It seems to me that all good cruising boats are still a bundle of choices and compromises. Fuel capacity is just one of many choices, with greater fuel capacity often coming at the expense of sailing performance.

I once met a cruising couple who had built a custom catamaran. When it came time to build the rig, they did the math and concluded that they could circumnavigate twice by burning diesel rather than buying the rig and sails 😂. And so, they built a “motoring” catamaran. That was mid 90s… maybe fuel was cheaper, or rigs and sails more expensive, or ecology less of a concern 🤷♂️.

I think it is possible to develop less dependency on diesel by honing your enjoyment of sailing, avoiding schedules, enjoying the slow passage of the scenery, and tuning up your solar generation game. That’s the ultimate in safety, relaxation, and the “off grid” lifestyle 🙂.

Absolutely agree with honing sailing skills and having a boat that sails well in a wide range of wind conditions. We hate motoring and are lucky that our Passport can sail with as little as 3-5 knots of breeze. If the seas are sloppy where that sails start slatting with that little wind pressure, we choose to drift rather than motor unless there is some safety reason to do otherwise. That’s why Wanderlust only has a little over 1,000 hours on the main engine after 11 years.

For me, not diesel, but solar is freedom.

On a catamaran, it is easy to install enough solar panels. Above the dinghy hoists, one can install 4x 440W panels, add a few more on the cockpit and/or salon roof, and you can get close to 3kWp. On ZwerfCat, this results in a charge current of 180 Amps. We cook on induction, have a freezer and two fridges, a watermaker, a washing machine, a hot water maker, 3D printer, etc. On prolonged rainy days we scale down, we don’t run the washing machine if it is raining, we can postpone making water until the weather improves, the fridges go automatically to a higher temperature as our drinks don’t need to be that cold anymore if it is raining, etc. We sold our generator (not only saving fuel but also maintenance and weight) and just use the engine in the rare case we need to convert diesel into electricity. In the 8 years we have this setup this happened about once per year.

About your motor graph: I see that if your engine runs at 1400 RPM instead of 2000, you save half the fuel. If you sail 6 kts at 2000 RPM, I bet you will sail at least 4 kts at 1400 RPM. With a lower speed you get a longer range for less fuel. In the rare case I use the engines other than manoeuvring at the anchor spot, I cap the speed to 4kts for this reason. If I want to go fast, I just select an appropriate weather window.

In the 5 years I have been sailing in French Polynesia, including 4 return trips between the Marquesas and Tahiti (upwind!) I used an average of 200 liters diesel per year.

For me, THAT is freedom. No noise, no smell, little maintenance, no big recurring fuel costs, and when the boat is not moving, we can stay indefinitely, we never run out of fuel.

If I was absolutely trying for the best range, I would look at lower RPMs but that’s typically harder on the diesel. And, running at lower RPMs can lead to carbon/soot buildup in the exhaust/turbo system. I should have put the torque curve in the article. For the 4JH4-HTE, maximum torque is just above 2000 RPM.

if you were custom building a bluewater boat for self sufficiency, you could have considered a none turbo higher capacity, low revving engine. Our 4.4L engine makes 86hp and our cruising revs for 6kts are 1200rpm. we use 3.3L/hr to move an 18t boat. it’s designed for low revs.

I agree that carrying all fuel in the tank is far better than in cans on deck. We see so many 40+ feet production boats with rows of 20L fuel cans on deck because the tankage is so small. this is not a good set up in heavy weather.

crossing oceans, we limit boat speed whilst motoring to 5kts. 1000rpm and 2.5L/hr. At this speed we can do 1000nm under engine. no cans on deck

Agreed, the speed vs power consumption curve is very important. At 1800rpm my 40ft cat does about 5.5knots in neutral conditions. I can double the fuel consumption (and power) to 24 or 2500rpm, but my speed will be in the 6.5 to 7 knot range. So double the fuel burn in this instance is only about 25% more speed. The returns diminish as we try to go even faster. It’s a priority based decision, and often dependent on the wind and/or current and whatever wind/sea/traffic/daylight conditions we are avoiding.

The returns from higher rpm are better when facing a headwind. If 15 knots on the bow slows me to 3.5knots, the extra fuel burn at 2400rpm for more power can become worth it since the hull resistance is no longer the biggest limiting factor to speed.

Also, why 1800rpmfor me? From what I’ve learned about diesels, 1800rpm is generally considered fast enough to avoid the detrimental effects of lower rpm and unburned fuel / cylinder glazing issues.

With your permission, let me highlight that in case of metric units, speaking of sailing it is more appropriate to use nautical miles.

I never heard of anyone going at sea using kilometers. 😉

Thank you. I’ve worked in metric units in the tech field but never in the sailing area. When I’ve had Europeans on board as crew, they don’t seem familiar with nm and ask me to conver to km.

And the “gallon”, could you translate it to the rest of the World: in your case it is 3.7 and not 4.5 liter one?

Unless I have a typo, I use 3.78 liters per gallon as the conversion factor. My formal training is in physics and I’m comfortable with both types of units but, as someone else pointed out, I may use “scientific” metric units rather than “nautical” metric units

That’s great that your approach works for your boat, but it’s anything but a one size fits all solution. We are almost the opposite on Stardust. Our boat sails well, and we have plenty solar with good batteries. Our 48 foot catamaran has a single 336 liter diesel tank and in over 18,000 miles of sailing we’ve never had any concerns about being low on fuel. For example, we sailed 4,018 miles from Panama to French Polynesia in 23 days, using 97 liters of diesel. I wouldn’t want a larger tank. There’s simply no need… that’s why we call it a “sail” boat.

As I said in another reply, I never meant to say our lifestyle and choices were the only correct way. It is a spectrum and each has to decide what is appropriate for them. On Wanderlust, we seldom motor and after 11 years, the main diesel only has a little over 1,000 hours. We are typically able to sail in as little as 3-5 knots of breeze and drift if we can’t. But if something does go wrong, I like knowing we have the range to get to safety.

I was also trying to highlight it’s not just about motoring range, though that is important. It also matters how long you want to stay in remote anchorages without having to worry about fuel. We’re back in FP now and, as you know, short winter days combined with several cloudy days can use up a battery bank. We also have ~1800 Watts of solar but, under those conditions, we still have to run the generator every few days. Now that days are getting longer again, we only run the genset once a week or so for a few hours to keep it in shape.

Nice article. It helps people think about the topic even if they choose a different method. Thanks for sharing.

Thank you! That’s always my intent. To get bluewater cruisers to think about what they’re doing with their boat, not just blindly following some advice that may or may not be relevant to their situation.

Having read most of it, I have to say that an article like this could well frighten and even scare inexperienced readers. Because there are other ways to do cruising. We have a 37″ sailing yacht. The main tank holds 150 litres and we have another 5 20-litre jerry cans that we fill up for crossings or in places where diesel is cheap. That’s usually enough for about one year, as we only use the engine to get on an anchorage or, very rarely, into a marina. Otherwise, we sail, because we have a sailing boat. And we use the new possibilities, such as Iridium and now also Starlink, to sail around calm areas, for example. On our last crossing, we had a sail ratio of 97.8% and in the Caribbean it was still 92.5%. Mind you, 99.9% of the time we use the hydraulic autopilot, as we don’t have a wind vane.

We cover all our energy needs exclusively with solar panels and one wind turbine. We have 800WP and lithiums with 400Ah. That’s enough for the refrigerator, water maker, autopilot, Starlink, notebooks, etc etc… Of course, this doesn’t work in a Norwegian winter, where we actually had to use our backup-Honda generator in 2023. But everything in summer and, from northern Spain onwards, also in winter, works perfectly with this configuration.

In other words, it works and you can be almost self-sufficient with very little fossil fuel. And it’s even fun to do it this way.

So don’t worry, there are simpler, cheaper and smaller options available. And perhaps the worries are smaller too.

I don’t disagree with you and I never meant to imply it can’t be done. The question I was trying to highlight and get discussion around are things like motoring range as a safety factor. My main goal was to get people thinking. I’ve seen too many new cruisers in the past 10 years or so that by a boat out of charter and try to do bluewater passages, then end up getting in trouble and having to be rescued.

We also take on crew from time to time and I hear the stories they have from other boats that run their generators multiple hours every day even when they have solar.

I would say your experience (nor mine) is the normal in today’s cruising world.

And I’m definitely not trying to scare anyone away from being a bluewater cruiser, but they should go into it with a healthy respect for the environment and also realize cruising the east coast of the US or the Caribbean can be very different than cruising remote atolls in the south pacific.

FWIW, and without passing judgement on a YouTube sailor, Tela Ru just posted a video 2 days ago about how they had to be “rescued” because they ran out of fuel at the end of a long passage. The video is here, https://youtu.be/99d7BioTBw0?si=_XbBZBeH3zQio_tG, and the relevant part is at about 12:30