Before starting the boat-buying process, I would have told you I expected it to be a bit like buying a car.

I thought we would visit some fancy marinas with a selection of boats on display, each with a price sticker in the window. We would kick, well, not the tires, but maybe the fenders. Perhaps ask a few pertinent questions (while having no idea what those might be), check a few online reviews and then decide that yes, this is the car… I mean boat… for us.

As many of us know, it turns out to be almost nothing like that. There are a million different ways it’s not like that. I now say that buying a liveaboard boat is a little more like buying a house; if the home you want to buy has been covered in tarpaulins, and everything has been disconnected for twelve months, including the sewers, power, and water.

While I think anyone who has purchased a boat will recognise our experiences, it’s worth pointing out that this article reflects our experience of buying a boat in the Mediterranean. At our broker’s advice, our boat was purchased using the terms in the MYBA (Mediterranean Yacht Brokers Association) contract, which is one of the yachting industry’s most widely used contracts. Other contracts with other clauses also exist and may be more common in other parts of the world; for example, beween two UK citizens in the UK.

First impressions

Our first misconception when buying a boat was that instead of visiting a fancy marina, it is far more likely that the boat you are interested in is on the hard. No one stores boats on a prime piece of waterfront. It’s usually an ugly piece of industrial foreshore or a dusty compound outside of town. Wherever it is, the hard will be covered in junk, bits of old machinery, empty oil containers and dusty boats in various states of maintenance or decay.

Not only is the boat you are there to see out of the water, but it has also had random wooden planks jammed against the hull to prop it up and prevent it from toppling over. It will be accessed by a rickety ladder that was stolen from another boat and will require a degree of gymnastic ability to not only climb it, but also pass safely onto its stern.

Once aboard, the next misconception we had to overcome was presentation. It’s like a house for sale, we thought; every boat will be staged to look its best. We were wrong. No one stages boats – at least not in our price bracket! Typically, the boat is filthy. This is partly because boat storage yards are harsh environments but mostly because cleaning boats is neither trivial nor cheap. Most sellers tend not to bother with cleaning in the early tire-kicking stages. No one will fly back to Greece to stage their boat at this stage.

Our experience has been that boats are usually presented in disarray. One still had the owners’ underwear strewn on the bedroom floor, another had half-opened containers of food in the kitchen, and empty condom packets in the drawers. Then there was the boat that had a child booster seat, still caked with food, attached to the salon table. Even if there’s nothing too outrageous, the cabins are likely to be full of cushions, sails and ropes and other boating paraphernalia.

In 2021, Covid-19 and Brexit added more pressure for sellers. Many owners, who had left for the season not expecting to sell, experienced financial and lockdown difficulties and decided to sell at the last minute but were unable to return to their boats.

Finding the right boat

The other reality is that there are typically very few boats with the key features and must-haves at the right price available for sale at any one time, so the need to present them well is greatly reduced. There is typically a very limited supply.

When buying a house, you buy by location. The houses available will likely be clustered together, so you can easily tour all of them in one afternoon. With boats, you focus on the models and features to produce a short list. That short list could be spread across the Mediterranean or even the globe. Early in your search, you might assume you would visit the boat before entering negotiations, but this can become expensive very quickly.

Boats suitable for liveaboard use are usually stored in isolated areas. This can be because it’s more attractive to cruise by boat there, but usually it is because it is cheaper to store the boat away from major regional centres. If you visited every boat of interest, you’d quickly waste a lot of money travelling to remote locations.

Inevitably, when you arrive, you will quickly find the boat is nothing like its description. According to every seller we have met, everything on their boat is 100% maintained and in excellent condition.

“It’s just that nothing is connected right now, so you can’t test it, but don’t worry, it’s the best conditioned boat of its kind in the world.”

“What do you mean, you want to see the maintenance receipts? Don’t worry about that, we have them but right now, we just don’t know where they are.”

More than one potential seller told us some variant of the above. After visiting a few boats, you start to see the benefits and cost savings of requesting some essential documentation and conducting some simple negotiations before you travel.

Sea trials and the negotiation process

Despite all these challenges, you will eventually find a boat that’s worth proceeding to survey and sea trial, which means the boat has to go back into the water. Moving a boat from the hard back into the water is not cheap. There’s probably some essential maintenance that needs to be done beforehand. Maybe the motors are in pieces as part of an overhaul and waiting on parts? And don’t forget the lift and launch fees.

The seller will want to know that you are serious. The MYBA contract requires you to agree on a price upfront and pay 10% of that as a deposit before knowing whether anything works. Then, and only then, will the seller launch the boat so you can confirm that it all works properly. Guess what – it won’t.

Back to our house analogy. It’s a bit like agreeing the price for a house, putting down a deposit and then paying for a building inspector and a plumber to come and inspect it. Just to make sure that the house is up to the standard promised. Remember that in this house analogy, you’ve only seen it with no gas, electricity or water and, of course, covered in twelve months worth of dust.

When the boat is in the water, your surveyor will inform you that this is not the best-conditioned boat on the market. Even if the seller was well-intentioned, it is a boat we’re talking about. Things break when they are not used. But then, things break when they are used too. Some things that are working may have reached the end of life and will need replacement soon. There’s always something.

You now have to decide. Do I buy it, or do I walk away? Under the MYBA contract, this decision is ideally made at survey and before proceeding to sea trial. At each step of the process, it becomes progressively harder to protect your deposit should you walk away. A good result, counter-intuitively, is an obvious, catastrophic failure. This makes the choice to walk a simple one. Once you decide to move to Sea Trial, the MYBA is explicit that problems identified during the survey are no longer reasons to reject the boat.

With the sea trial complete, the next step is to inspect the boat out of the water. At this point, as the potential purchaser, the MYBA says you are the one who must pay to have the boat lifted so that all the systems you couldn’t get at while it was in the water can be adequately inspected.

“But”, you might say, “surely you’d check those when the boat was out of the water before the survey started?” Sadly, this is not part of the standard MYBA contract, although a reasonable seller might allow it.

If you find additional problems once out of the water, you will need to show that these are unrelated to any items you could have identified earlier in the survey process. At this point, it is very hard to walk away without losing your deposit.

If you do decide to walk away, you might still spend time arguing over the return of your deposit. In our case, for a boat that would not even start when it was launched, the seller argued we should contribute from the deposit to the cost of the launch. Once our lawyer was involved, the deposit was returned. The MYBA does a good job of protecting both parties, but it is very pedantic and quite specific.

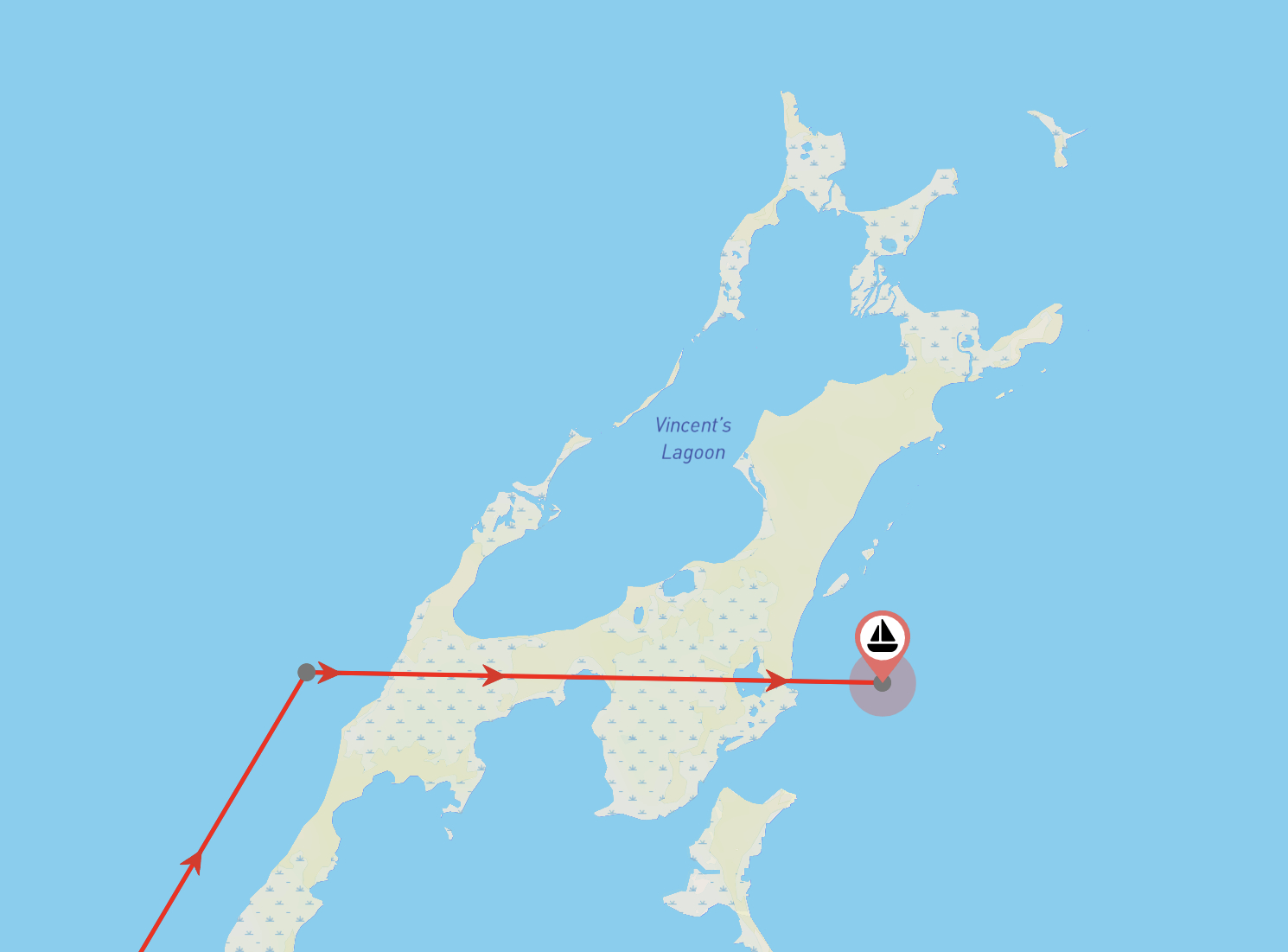

The last journey for the previous owners aboard Matilda as we head back to the dock.

All of this takes time, so perhaps you decided to move things along by going to sea trial with several boats in parallel. Good luck with that. Remember, for each one, you’re locking 10% of the purchase price down in a deposit.

In chatting with other liveaboards, the process of buying a boat can vary, but in general, when buying a boat in the Mediterranean under the standard MYBA contract it works something like I’ve described above.

So what next?

It turns out that buying a boat is nothing like buying a house or a car. While it’s actually more fun than I may have made it sound, it’s definitely not straightforward!

Inevitably, it turned out that the buying process was the simple part. Next, you just have to insure it, maybe reflag it, maintain it, upgrade it, repair it.

So congratulations, you’re now the proud owner of a boat. And most of us wouldn’t change that for the world, regardless of the challenges along the way.